Reed Pop put on another incredible Comic Con this year with lectures, premiers, and new technology that tested the capacity limits of the Javits Convention Center in New York City. Reed Pop handled the massive influx of over 200,000 passionate attendees, who consumed every morsel of content being offered from artists, writers, musicians and studios from around the world, without breaking a sweat and that’s what makes this truly an incredible event.

We are always on the lookout for multimedia trends, storytelling threads and innovative ways to create and distribute content. Unlike the multitude of other conventions we attend every year, Comic Con offers a unique approach and allows us to interview content creators that we normally don’t cross paths with. Whether it’s Howard Shore, brilliant artists from the show floor or some of the passionate attendees, Comic Con always leaves us wanting more.

As with 2017’s NYC Comic Con, Virtual Reality made its presence known with several booths dedicated to the dynamic new technology. However, instead of just replicating travel experiences or well-known landmarks, storytelling entered the picture. Robert Rodriguez held court at the convention with his son and actress Michelle Rodriguez, to showcase his new VR short, The Limit, a first-person “immersive cinema experience.”

Michelle Rodriguez, no relation to Robert or his son Racer, plays a genetically enhanced weapon who turns the tables and goes after the people who modified her for financial gain. “I love the visual aspect of storytelling,” Robert Rodriquez revealed, “like comics and video games. The next level of video games is VR, and I wanted to do storytelling in VR. I always wanted to be an early adopter, so we started the company RR (double R) to help drive the VR industry faster.” Once the company was created, they teamed up with STX Entertainment to develop The Limit, and explore other possibilities using the technology. “What really makes VR believable, is the 360 degrees of sound design,” Racer stated. “While the visuals allow you to explore the entertainment in a very personal way, it’s the sound that allows you to buy in.” For Sound Designers out there reading this, VR looks to be a major trend and it’s not too early to get ramped up on this dynamic tech.

The Limit premiered a trailer for the audience, which showcased several action scenes in which Michelle’s character was interacting directly with the participating viewer, in this case by looking directly into the camera lens. “It’s interesting, half the time, when you are acting, you are doing your best to avoid the camera,” Michelle Rodriquez confided, “now my co-star IS the camera.” The trailer depicted a motorcycle chase, skydiving and, of course, some hard-hitting hand-to-hand combat.

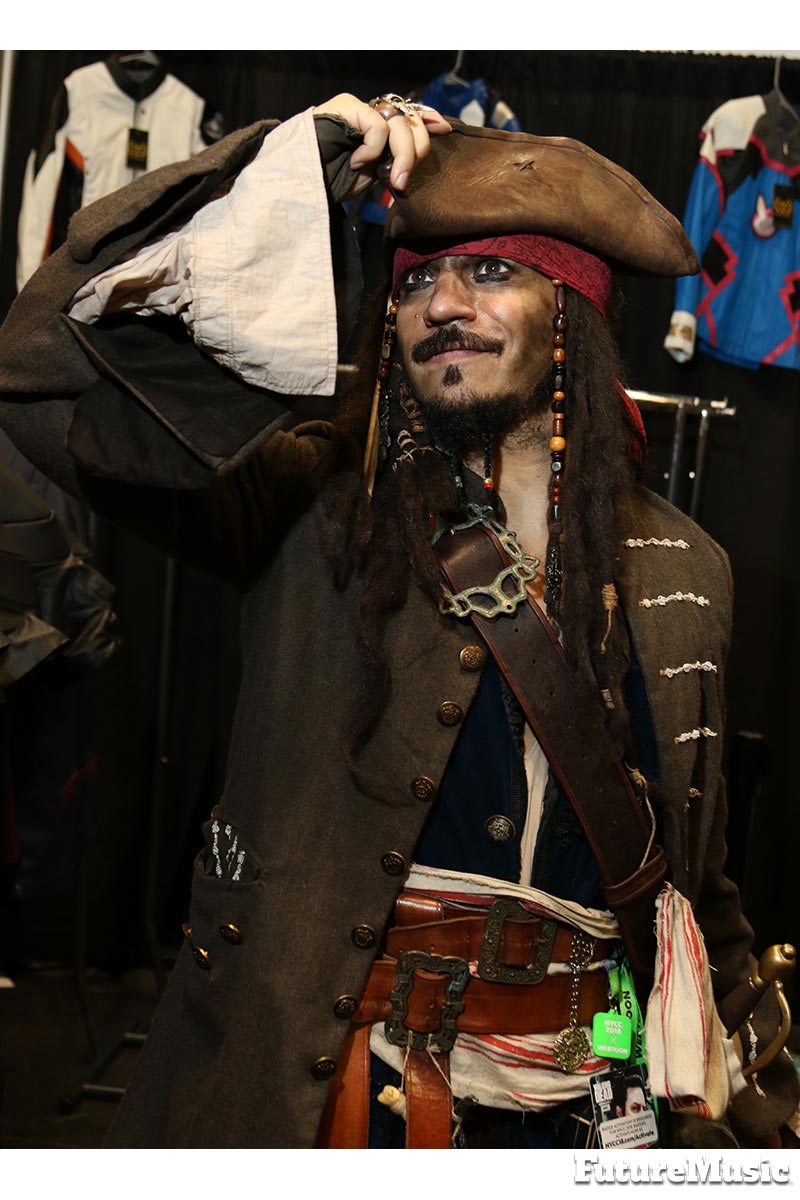

“Be yourself because everyone else is taken.” —Capt. Jack Sparrow Cosplay

FutureMusic’s Editor, Dan Brotman, was able to speak to Jack Norman a VR sound designers at the convention, to learn more about how he approaches creating soundscapes for multidimensional worlds. “Authentic reverberation is paramount,” Norman explained, “if spacial conformity is off, the user ‘feels it’ immediately, and the suspension of disbelief is lost.” Norman also gravitates to utilizing real world sounds and manipulating them in post, as opposed to synthetic textures. Sound is critical for creating a convincing virtual reality experience because of the key role that audio cues play in our sense of being present in an actual, physical space.

ComicCon offers us a very unique opportunity to speak with sound design developers who are on the forefront of film, television and interactive virtual reality technology. Three-dimensional audio is critical for creating a believable virtual world, and sound design for VR is very different from traditional games or movies. VR audio techniques, including building immersive ambiences, attenuation curves, mixing and player focus, is something we were able to discuss with many different filmmakers, including Rodriguez, and we learned some incredible tricks for getting the most out of this new medium.

“Human beings have two ears, but are able to locate sound sources in three dimensions.”

According to our discussions with Oculus, who referred us to their documentation, humans rely on psychoacoustics and inference to localize sounds in three dimensions, including factors such as timing, phase, level, and spectral modifications. Laterally localizing a sound is the simplest type of localization, as one would expect. When a sound is closer to the left, the left ear hears it before the right ear hears it, and it sounds louder. The closer to parity, the more centered the sound. In Virtual Reality, listeners may primarily localize a sound based on the delay between the sound’s arrival in both ears, or interaural time difference (ITD). Or we may primarily localize a sound based on the difference in the sound’s volume level in both ears, or the interaural level difference (ILD). The localization technique we rely upon depends heavily on the frequency content of the signal. We also key on the difference in time of the signal’s onset. When a sound is played, which ear hears it first is a big part of determining its location. However, this only helps us localize short sounds with transients as opposed to continuous sounds.

Front versus back localization is significantly more difficult than lateral localization. We cannot rely on time differences, since interaural time and/or level differences may be zero for a sound in front of or behind the listener. Humans rely on spectral modifications of sounds caused by the head and body to resolve this ambiguity. These spectral modifications are filters and reflections of sound caused by the shape and size of the head, neck, shoulders, torso, and especially, by the outer ears (or pinnae). Because sounds originating from different directions interact with the geometry of our bodies differently, our brains use spectral modification to infer the direction of origin. For example, sounds approaching from the front produce resonances created by the interior of our pinnae, while sounds from the back are shadowed by our pinnae. Similarly, sounds from above may reflect off our shoulders, while sounds from below are shadowed by our torso and shoulders.

A direction-selection filter can be encoded as a head-related transfer function (HRTF). The HRTF is the cornerstone for most modern 3D sound spatialization techniques. How we measure and create an HRTF is described in more detail elsewhere in this document. HRTFs by themselves may not be enough to localize a sound precisely, so we often rely on head motion to assist with localization. Simply turning our heads changes difficult front/back ambiguity problems into lateral localization problems that we are better equipped to solve.

All these factors go into creating believable sound design and atmospherics for virtual reality, which goes way beyond simply using localization. For more information about composing and sound design, follow us on social media.

Well, that wraps up this year’s coverage of ComicCon 2018. See you next year!